WPA in Motion: Reflections from Inside a Shifting Arts Institution (Part 1 of 2)

By Jordan Martin, Curatorial Production Manager

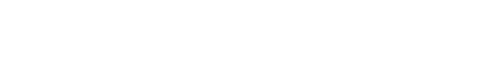

Since its founding in 1975, Washington Project for the Arts (WPA) has evolved alongside the city it calls home—shifting in response to artistic movements, political moments, and the needs of its community. This two-part blog series captures a recent chapter in that long history, through a candid conversation between three team members—Alexandra Silverthorne, Nathalie von Veh, and Jordan Martin—who helped shape WPA’s artist-organized program model, officially introduced in 2018. Part 1 explores their personal journeys into the organization and the broader changes unfolding in Washington, DC’s arts ecosystem. Part 2 turns inward, documenting how collaboration, care, and experimentation became foundational to WPA’s evolving model. Together, these reflections offer insight into what it means to be part of an institution constantly in motion.

*****

Part 1: Joining the Current: Personal Histories Within WPA’s Ongoing Legacy

Every person who arrives at WPA steps into something already moving. The organization has been around for decades, constantly shifting alongside the city and the artists who shape it. In Part 1 of my conversation with Alexandra and Nathalie, we talk about how each of us first found our way to WPA, and how those entry points were influenced by what was happening in DC at the time—politically, culturally, and creatively. From early impressions to the realities of a changing arts landscape, this part of the conversation looks back at where we started, and the broader cultural and spatial shifts that shaped the city and WPA in the 2000s and early 2010s.

Jordan Martin:

I want to talk about your first impressions of WPA. Nathalie, I know you started working here right after undergrad, and Alexandra, as a Washingtonian, I’m curious if you had any understanding of WPA before beginning your job here. I’d like to hear your first impressions to understand how you both arrived at WPA.

Alexandra Silverthorne:

It’s a good question, I think. When I graduated from undergrad in 2002 and moved back to DC, I was heavily involved in anti-war organizing and community work until around 2004. It wasn’t until 2004 that I started getting back into my studio practice. That’s when I began finding out about shows during the peak of blogs. Everyone had their internet blogs, and WPA was all over them.

In 2005 or 2006, I met Kim Ward, who was the executive director of WPA at the time. I’m trying to remember the first show or project I attended there, but I can’t. It felt very formal because it was more exhibition-driven, and there was a membership aspect as well. The exhibitions were often in raw or in-between spaces.

Even though I was exhibiting and knew some of the artists in WPA shows, it felt like I was “here,” and they were “there”—almost unattainable in a way.

Jordan Martin:

Before that, though, was WPA ever in your periphery?

Alexandra Silverthorne:

No, I mean, it wasn’t. I left when I was 15 and came back at 22, barely home in between. We spent a lot of time when I was a kid at the Hirshhorn, the National Gallery, and the Smithsonian Castle. But I don’t remember going to galleries or alternative art spaces as a kid. I don’t know why, necessarily.

Nathalie von Veh:

So, I was 21, finishing my undergraduate degree at AU, and took a drawing class with Zoë Charlton (Zoë later served as a WPA Board Member, 2017-2025). After studying abroad for a year, I was majoring in international studies and minoring in art history, feeling increasingly drawn to the art department. As graduation approached, I found it hard to visualize a future in international relations. Wanting to make connections, I began to fall in love with DC, still caught in the undergraduate AU bubble. Zoë, a practicing artist, suggested I apply for an internship at WPA.

I started interning there in January of my final undergraduate year. My first experience was somewhat surreal—I interviewed at the Capitol Skyline Hotel and knocked on a hotel room door, unsure of what to expect.

It was a transformative time—I learned about WPA and met artists who had called DC home for years. I worked on the Hothouse Video: Jacolby Satterwhite in 2014, bartending for the opening. Eager to learn, I absorbed everything.

My supervisor, Deena Odelle Hyatt was active in the music scene. Through her, I started attending shows and made friends in the DIY music community. My time at WPA connected me to both the visual arts and music scenes, fostering lasting friendships in an interdisciplinary community.

Alexandra Silverthorne:

I think one thing you said that’s interesting is just being a sponge. You were 22, and I was 24 at the time. I had met tons of people through activism work, but not as many artists. I would go after work, hop on the train, and visit a gallery in Bethesda, or go from Dupont, where my office was, to see art on my lunch break. At that time, there were so many galleries in Dupont. I’d take my lunch break to see art and send emails about it to other artists I knew. That sponge-like phase of our lives is so influential for understanding how a community works and for making those important connections.

Jordan Martin:

Yeah. So, when you both started at WPA, your first time interfacing with this DC arts nonprofit, what stood out to you about how WPA operated? How has that changed for you over time?

Alexandra Silverthorne:

Am I going first again? As an Aries, I’m happy to go first! WPA was leaving the Corcoran when I started applying to grad schools in fall 2007. After volunteering with WPA, I reached out to Kim about a programmatic internship to shift away from administrative nonprofit work.

It was an exciting time. The WPA office at the Corcoran was the size of our storage closet, and Adam Griffiths had a desk in the curator’s office, which I could use at times, but otherwise that was it. So, it was thrilling to have our own space at 2023 Mass Ave in a townhouse next to the hotel.

There was a lot of excitement around WPA. I don’t want to say it was just about WPA leaving the Corcoran, but there was fresh energy coming into the organization. I don’t remember if there’s a follow-up to it, but—

Jordan Martin:

Well, how have you witnessed that feeling change over time?

Nathalie von Veh:

Yeah, I think the organization has gone through many iterations in the decade I’ve been involved. It has its own cycles. When I first started, we were at the Capitol Skyline Hotel, activating the lobby and showcasing art wherever possible due to limited space.

Within my first year and a half at WPA, we launched a capital campaign to move into our own space on 8th Street, near the 9:30 Club and Howard University, which we just left a year ago.

This transition let us focus more on our programming without worrying about where to show work, allowing us to clarify our operations and support the artist community.

Recently, we’ve been working nomadically again, learning how that impacts our work and facing new challenges—though they aren’t entirely new to us. I agree with Alexandra that we’ve prioritized artists and their needs over simply seizing every opportunity with limited resources.

Part of this shift wasn’t just due to our resources, but also because DC experienced significant changes between 2010 and 2017. Access to spaces and artist-run venues was threatened, and we lost a lot. When I got involved in DC’s art scene, it was at the end of a vibrant period filled with blogs, artist-organized shows, and rich DIY history.

It felt exciting to be part of that, but we also had to fight for spaces as people were being pushed out. Artists, as we know, were involved in that wave of gentrification, complicating the loss over time. That’s why we started to rethink what space meant as a resource and how to give artists more agency, preserving artist-organized culture in DC.

Alexandra Silverthorne:

And also, yes to all the artist-organized projects and DIY, which are such an important part of DC’s fabric and history. More commercial galleries were closing then, and the places to see art were being cut down. There were all these galleries in Dupont. ConnerSmith was there at the time; it was an anchor for the community. First Friday in Dupont was also a cornerstone of the local arts scene. But later, even the opportunities to exhibit art—everything from high-level galleries to artist-organized events—were being reduced.

Jordan Martin:

I appreciate the framing of the change within WPA as not just linked to the new space on 8th Street, but also as a response to how much was lost. I’d say it started maybe around 2008, but from 2012 to 2016, it felt like things were getting really dire. It was as if everything was slipping through our fingers. You’d walk down the street or get a text from a friend saying, “Hey, the landlord is kicking us out, and we have like 30 days to move.” That was a hub site, and then it was just gone. Next, you’d see construction happening, and it felt like everything was erased just like that.

I joined WPA at the beginning of 2017. I think I interviewed at the end of 2016, and my first day was January 2017. I always get that wrong.

Nathalie von Veh:

Yeah.

Jordan Martin:

And the WPA had a new Executive Director because I grew up hearing about WPA, but it was often discussed as though it was not a space for me and my peers. I remember going to the Emerge Art Festival and meeting Black local artists, which was refreshing. However, even as a fourth-generation Washingtonian, my family and community didn’t know the organization—it wasn’t on our radar. When I learned from a friend that they were hiring, I hesitated, wondering how I’d fit in given that my DC experience is very Black.

I questioned how it was possible to support local artists in a space that felt so white. But when I heard about the new ED and the intention to be more intentional and contemporary, I decided to apply. Joining the team, there was a startup energy and a desire to work differently than before. Instead of traditional exhibitions, we aimed to move away from formality, though the ED’s vision was still developing at that time. I was figuring things out as I went.

I’d like to hear your thoughts on the 2017 period when I joined; things feel fuzzy about the program model. I was hired as an assistant and given tasks, but it wasn’t until a year later that I took more ownership of programs. Can you share your experience during that time—what the organization’s mission and motivations were?

Nathalie von Veh:

That was definitely a time when we were rethinking how the organization could be more relevant, contemporary, and intentional. We focused on addressing racial divides and what WPA represented; we were less interested in replicating past expectations and more focused on what made DC special as an artist’s home. Our goal was to serve those engaged in experimental, collaborative work.

At the time, many DIY and artist-run spaces were disappearing, pushing artists out of the city. Some moved to Baltimore, LA, or New York. While change isn’t necessarily bad, we were concerned about what DC would lose if that trend continued.

You’re right to say we were in a startup phase, exploring how to elevate the DC art scene. This included not only serving local artists but also working with artists from outside the area. Building communities and relationships is a core value for us. It’s not just about a short exhibition; it’s about helping artists gain professional experience, organizing skills, and networking opportunities that may be hard to access without support.

We aimed for artists to leave with lifelong friendships, collaborations, or research partners from their time at WPA. We made it clear we weren’t just a house venue; we had different resources. We were critically thinking through all of this. When you joined and we interviewed you, we were excited because you shared our desire to think and move differently, seeing you as a creative partner eager to reshape our programming.

At that point, we didn’t have all the answers; we were questioning and conceptualizing everything. We offered our space to artists and organizers to meet the moment. A lot was happening in 2016–2017—protests, anger, and organizing. We listened and tried to use our platform to explore what artist-organizer, artist-driven programming could look like. But it wasn’t until you joined the team that we started clearly outlining the process for artists to engage with our program model.

Alexandra Silverthorne:

I think what you said, Jordan, about WPA feeling like a scrappy startup is really interesting. It’s at a 50-year anniversary, but WPA has always been a bit of a scrappy startup. The organization is often reinventing itself based on available resources, artists’ needs, and what the city requires. Every few years feels like a new scrappy startup phase. To Nathalie’s point about the space, having that structure allows for flexibility. Instead of just asking, “What do we want to put in our gallery?” we’re thinking, “How do we want to use it?” Of course, who knows what would have happened if the 2016 election had gone differently. We might still have moved away from traditional exhibitions, but opening the space for artist-organizers to build community connects to that idea of “Make your own art scene.”

Jordan Martin:

I’m happy to hear that reflected back, because it’s wild that we’ve never really talked about the transition from when you started at your respective times, to that shift at the end of the biggest wave of gentrification and WPA’s response. It’s interesting to think about my own feelings when I joined, especially around 2018, when we were beta testing a new program model. The language was tricky; we wanted it to align with our actions and aspirations. “Artist-driven” was a term we considered, but we felt more confident in “artist-organized.”

During 2018 to 2019, we were revising the mission and vision, which took time and education with the board. I remember trying to visualize this as a flow chart, figuring out how to represent the artist-organized process. I want to hear from you about the moments that stood out during this period of beta testing, like setbacks or confusion, but also the times when we realized why we created this model. While it’s a big question, it encapsulates our journey from beta testing to a more solid structure and the challenges and successes along the way.

Nathalie von Veh:

I think our first foray into artist-driven programming was with Sheldon Scott on a citywide performance campaign (Sheldon For DC, 2016).

It was truly experimental for us. We wanted to put an artist in the driver’s seat, allowing them to say, “I have this idea and need to build a team around it.” We didn’t have much structure at that point, so we said, “Okay, Sheldon, you have an idea.” We aimed to push the project beyond just Sheldon curating himself, establishing it as a collaborative effort that included other artists and community members. This project helped us build relationships throughout the city. That was the beginning.

End of Part 1 (Part 2 Coming Soon!)

*****

Hearing Alexandra and Nathalie talk through their early memories of WPA and the shifting landscape of DC’s art scene really grounded our conversation in something personal, but also political. It reminded me how our individual paths into the organization were shaped by broader forces: disappearing spaces, changing neighborhoods, and evolving ideas about who arts institutions are for. In Part 2, we dig into that shift: how we started rethinking WPA’s role, experimented with a new way of working, and slowly built what would become our artist-organized program model. It wasn’t always smooth, but it was deeply collaborative, values-driven, and shaped by the urgency of the moment.

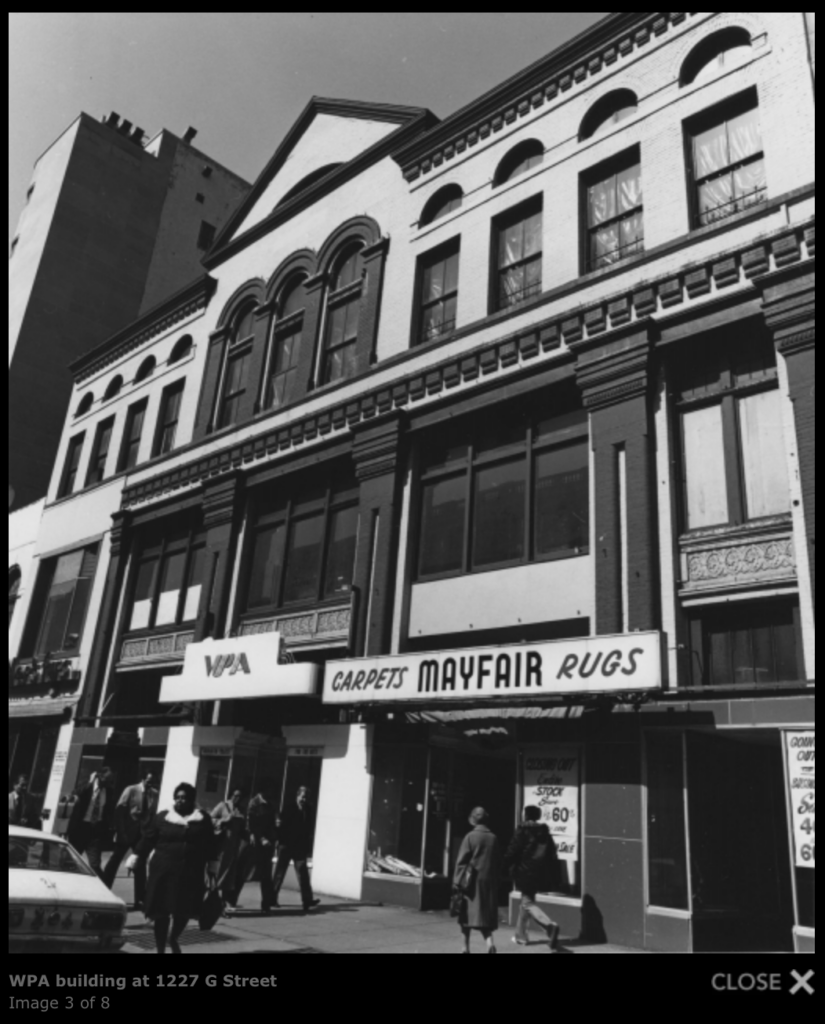

(All photos are courtesy of WPA’s archives.)